The Star Wheel on Match Game ’78

A case study analyzing Match Game's management intervention to enable equal screen time. Management lessons include stakeholder management, action planning, and closing feedback loops.

[If you would like to support the development of more management material, you can support with a cup of coffee.]

Match Game, a panel game show, existed in several iterations from its start in 1962 (NBC) to the 1970s (CBS) to the current iteration on air today (ABC). Gene Rayburn, the incomparable host of the first few iterations, was masterful at entertaining contests, celebrities on the panel, as well as audiences in the studio and at home.

In 1978, Match Game introduced “The Star Wheel” in order to make the screen time for each panelist more equitable. The intervention from producers would be a turning point for the show and one of its most celebrity panelists.

The Mechanics of Play

Gene Rayburn served as host, making small talk with each of the two contestants, and engaging in comedic banter with the panel of celebrities.

In total there were 3 game segments: contestant vs contestant, super match, and celebrity head-to-head. In the first segment, contestants competed against each of other — the objective was to secure the most matches (up to 6) with the panel.

There were 3 game segments, contestants competed against each other in the first segment to match the celebrity panel. Host Gene Rayburn would pose an open-ended question to a contestant (e.g. Johnny always put butter on his ___) while the panel wrote their answers in secret on post-sized cards.

After the buzzer for time, the contestant provided their answer and received 1 point for each celebrity match. Contestants played two games in this segment until 6 points were reached. The winner went on to compete in the next game segments: super match.

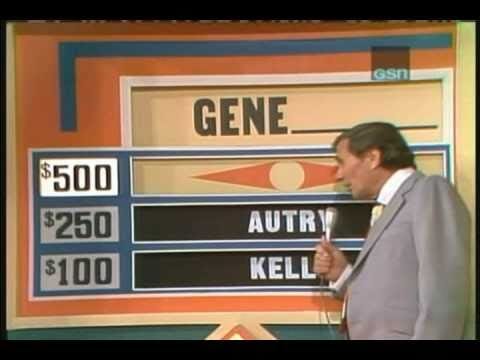

In super match, contestants were shown a short phrase or word accompanied by an empty space. For example, “Gene ___” would have 3 slots based on the most popular answers from a studio audience. The contestant would choose 3 celebrities from the panel to solicit answers. The contestant chose from among the 3 provided responses or could chose their own response. The top answer was worth $500, the second $250, and the third $100.

A successful contestant in super match could win ten times that amount by correctly matching 1 celebrity (of their choice) win the celebrity head-to-head. The final question, similar to super match, was a “fill in the blank” type of question.

A Sea of Talent

In Match Game’s initial run in the 1960s, there were just two celebrities on the panel and the tone of the show was family friendly. As part of its relaunch in the 1970s, the show moved to a new network (NBC to CBS), incorporated much more provocative questions and featured more raucous participation between host, contestants, the panel, and the studio audience.

As part of the refresh, the panel was expanded to 6 celebrities with many serving as episode regulars and often recurring guests. Richard Dawson, the future host of Family Feud, was one of the first Match Game regulars along with Brett Somers and Charles Nelson Reilly. Richard always occupied the middle seat in the bottom row while Somers and Reilly maintained the middle and right seat of the upper row, respectively. Seat-mates Somers and Reilly regularly played off each other as a “bickering couple” though Reilly was openly gay.

Panelists appeared one-week at time (matching the show’s production schedule) and sat in a set consistent order: the male guest panelist of the week sat in the upper left seat, Somers, Reilly, the female guest panelist of week sat in the lower left seat, Dawson, and a female semi-regular guest sat in the lower right seat. The panel was gender-balanced throughout its run.

Celebrity guests included Betty White, Isabel Sanford, Joan Rivers, George Kennedy, Fannie Flagg, Jack Klugman, Nipsey Russell and other stars of television and film of that era. Rayburn usually shared on-air kisses with the female celebrity guests and included on-air flirting.

Tasked with reading the questions and building rapport with contestants, Rayburn and his writing team including questions intended to build audience participation. One common question would start with Rayburn stating “Dumb Donald / Dora was so dumb …” and the in-studio audience asking “How dumb was he / she?” before the rest of the open-ended question was finished.

Among the other show norms, Rayburn also encouraged the audience to boo bad answers from contestant and panelist and to jeer risqué answers. Censorship in the 1970s and 1980s forced panelists and contestants to get creative with their responses as Rayburn regularly threaded the needle between contestant, panelist, and in-studio audience similar to a conductor leading an uproarious production. Rayburn wasn’t shy about telling contestants about “rotten answers,” something the studio audience was receptive to and enjoyed.

A Rising Star

Similar to most cultural norms, there is universal benefit until those norms decrease equality. The nature of television — its transparency for what is seen on-screen and its lack of pay transparency — often creates management problems stemming from managing the priorities of on-air talent.

On a typical episode, each of the 6 panelist during main game play would average about 60 seconds of screen time per 3-game episode (~8% of show run time).1 During super match, each of the 3 panelist would average 8 seconds of screen time. Dawson, Somers and Reilly were among the most frequently chosen panelists (cumulatively, that totaled 9% of show run time). For the head-to-head match, Dawson was by far the most frequently chosen celebrity.2

A celebrity chosen for both super match and head-to-head match could hold nearly 10% of screen time per aired episode. The average airtime of an episode was just over 20 minutes. Episodes of most televised game shows typically were edited down from a longer taped portion. If we zoom out to look at the production schedule, which includes taping 5 shows back to back, the smaller differences in screen time add up.

The disproportionate time and attention paid to Dawson by contestants was noticed by viewers and impacted other regular panelists. Match Game was also a syndicated show, meaning viewers could watch re-runs and contract talent often receiving residual earnings from each syndicated re-run.

Dawson would leverage his on-air popularity to land an audition to host Family Feud. It has been suggested that he threatened to remove his humor and wit from Match Game until he was guaranteed the opportunity to audition. He secured the host position of Family Feud in 1976 while concurrently filming on Match Game. Of note, Match Game was broadcast on CBS while Family Feud broadcast on ABC.

> Management Time Out >

Let’s use this moment to take a “management time out.” Let’s pause to understand what information we currently have, what we might hypothesize are the likely outcomes, and how best to plan ahead.

Identifying incentives & stakeholders: You are the producers of the show, what are your incentives? Whose interest will you (and should you) prioritize? How will you weight considerations from each of the following stakeholder groups:

Audience / viewers: In most of entertainment, viewership translates to advertising dollars return to the show as revenue. What was important to the audience and what would increase viewership? What priority should this be for a producer?

Host of the show: On many shows, the host is the “primary” talent that anchors the show and in some instances may set the direction of the show, suggest improvements, or serve as part of the group of producers for the show itself. What was important for Rayburn to do his job well? What priority should this be for a producer?

Full celebrity panel: On panel shows, there is rarely an explicit hierarchy (outside of appearing first in the credits). Compensation may vary. Panelists may be “staffed” to promote a show or movie (including for the network hosting Match Game, CBS). What was important for the panel to do their jobs well? What priority should this be for a producer?

Richard Dawson: The most popular panelist for the show, his impact on production was larger than other panelists. What was important for Dawson to do his jobs well? What priority should this be for a producer?

Framing the problem: Now that you are clear on each stakeholder group, their priority to you and your goal (as producer/manager), how do you determine what the tipping point for change is? Is it number of complaints from other judges, is it host dissatisfaction, do you conduct a focus group (and with whom)?

Developing an action plan: If you’re a producer, do you interview the other judges? If so, do you prepare a consistent set of questions for each and do you provide them the questions in advance? Are you clear on what you want to know, what pieces of data you need to determine which of the options under consideration would make sense? Have you thought through what your interviewee might be comfortable putting in writing and what is best kept as a verbal discussion?

Contingency planning: What happens if any of the talent threatens to walk away?

Closing the feedback loop: Once you’ve decided the best intervention, what is your communication and measurement plan?

The Star Wheel Debut

In June of 1978 producers introduced The Star Wheel. Contestants advancing to the head-to-head match would spin the wheel (divided into 6 sections with the names of that episodes celebrity panel) to determine who they would work with next.

Mathematically, each of the 6 panelists had an equal chance of being chosen. The wheel also included segments within each of the divided sections. For example, if a full wheel had 30 slots — with 5 corresponding to one celebrity — a contestant might land on a “bonus” slot that multiplied their payout.

In the first episode to feature The Star Wheel, chaos erupted among the panel and in-studio audience as the wheel landed on Richard Dawson (starting at minute 7 of the below video).

The Aftermath

Later in the 1978 season, Dawson would request to be released from his Match Game contract to focus solely on Family Feud. With producers refusing his request, Dawson turned down his charm and rapport with contestants, and stopped speaking with his other celebrity panelists.3 That same year Dawson was released from Match Game. Dawson would go on to turn Family Feud into a success as its host through 1985.

Match Game 73 - 79 includes 1455 episodes along with the PM version (230) and syndicated show run (525). Rayburn hosted the revival of the show in 1983 (after its cancellation in 1981). The show has been revived 4 times since then and currently airs on ABC with host Alec Baldwin.

>> Real World Application >>

Case studies are intended to serve as exemplars and models to be applied in the real world. Cases are intentionally nebulous and will not always provide clear lines for what to do — and in some instances the case may provide an example of what NOT to do. Using the comment section below, weigh in on these questions:

What lessons about attempting to create an equitable work environment can be gleaned from “The Star Wheel”? Are there some instances where such an intervention 100% makes sense, or instances where this solution might backfire?

How might a similar scenario show up at work or on a team? What do you do, as a manager, if you have a “Richard” on your team? And how do you manage for your whole team’s satisfaction — and is that your goal?

If you would like to support the development of more management material, you can support with a cup of coffee.

Timed calculations from extrapolations watching, Match Game 76 episode 619.

Biography of Richard Dawson, IMDb, trivia section.

Coworkers who Struggled to get along, Mental Floss. February 2008.